ARSyd

On March 30 I’ll be giving a talk at ARSyd, an event in Sydney on, you guessed it, Augmented Reality. I’ll be talking about my research project broadly, but will be focusing on the mobile/situated aspect of knowledge generation. Here’s a (regrettably third-persion) abstract:

The lines between the digital world and reality are increasingly blurred. In his PhD research at RMIT in Melbourne, Chris studies how natural environments are being augmented with digital information, and how this information can be used in-situ to generate novel insights about the places we inhabit. He will discuss how mobile and AR technology can be used to interpret information that is about place, and will give an overview of his project designing a location based knowledge system for national park rangers.

If you’re in Sydney it’d be great to see you there. Map and further details are over at eventbrite.

Metabolism, the city of the future

Following on from the recent city/space theme is a new exhibition at Tokyo’s Mori Art gallery in Roppongi Hills entitled “Metabolism”.

Metabolism is an architecture movement that started in Japan in the 1960s. From the press release:

Metabolism which sprang up in the 1960s remains the most widely known modern architecture movement to have emerged from Japan. As its biological name suggests, the movement contends that buildings

and cities should be designed in the same continuous way that the material substance of a natural organism is produced. This is the first exhibition in the world to provide such a comprehensive overview of the movement.Models, archive film footage, and 3D computer graphic images of grand visions of future cities held by the architect

Tange Kenzo, as well as Kurokawa Kisho, Kikutake Kiyonori, and others who had come under the influence of Tange, and their experimental architecture which has become a reality in today’s cities, will be exhibited for exploration of their meaning from a current perspective.

It looks like it’ll provide some great insight into how the future was imagined, in the past. It would be interesting to see how (if at all) the digital world was thought of when designing this then new type of Urbanism.

The exhibition runs from July through to August, 2011. If you happen to be in the neighbourhood you should definitely check it out.

Code/Space

Code/Space is a body of research that looks at the creation of space through technology. Similarly, it looks at how technology is transforming the relationships people have with places, such that traditional separations of virtuality and reality may no longer be necessary.

It’s another thread of ubicomp research, except this time with a geographical focus. Nice.

Virtual Spaces

One of my favourite blogs at the moment is UrbanTick, run out of University College London. It’s a good mix of technology, architecture, environments and of course, people. It particular its a great source of geographical visualisations: representations that sit at the intersection of all these things.

Visual Cities is my latest discovery through that blog – visualising geocoded twitter and flickr data. Its creator states: “By revealing the social networks present within the urban environment, Invisible Cities describes a new kind of city—a city of the mind”.

This touches on what I think is the core of my phd: the representation of knowledge about locations – that the world that exists in our minds, and the one that is created socially, is not necessarily evident in the environment, but exists physically on servers across the world, and virtually in a meta-layer above our heads.

One interpretation of ubiquitous computing is that there is potential to incorporate this information back into the environment, removing the dissonance between space and our understanding of it. Visualisations are a step towards that: towards making the abstract tangible and actionable.

Reuben, who I’ve been working with for a few years on a number of things, also talked about this and built his own simple geo-visualisation for the iPad, framing it as an “historical narrative”.

Together we’ve been building a tool that will allow people to create their own meta-data about places, and collectively manipulate and interpret this data to create knowledge. The more I think about the different strands of my research, the more I see them converging. After about a year of fuzzy directions and more questions than answers, its relieving to see a somewhat clear path is emerging.

Nokia Lenses

The need to make sense of an ever-increasing stream of data has never been greater, especially in a mobile context. At Mobile HCI’10 last year, a team from Nokia research presented a prototype solution for feed aggregation, dubbed Lenses. This allows people to curate their own stream of content relevant to different purposes – different self-generated contexts.

From the paper:

Lenses explored the need for a universal inbox and the value in interacting with fine-grained filtering mechanisms of content on a mobile phone… [It represents] an alternative to the application paradigm where people can engage with their data using different perspectives such as topics of interests, tasks, or roles in their life.

How could these be more closely tied to location, and made sensitive to context?

Context: awareness vs sensitivity

I’ve been doing a lot of reading and writing around context awareness the past couple of months – so much so that I changed the subtitle of this site to include it. It’s safe to say that the notion of this kind of awareness completely captured my imagination, or at the very least, led me to line up a whole stack of journal articles and books on the topic.

With the plethora of location-based applications appearing on various mobile platforms, the ubiquitous nature of geo-tagged data and the popular medias seemingly undying thirst for the latest tech-innovation, location enjoyed a pretty good ride in 2010. Starting at location as a focus of research (as I did), it’s not long before you realise that a coordinate is just one piece of metadata that can describe context, and it seems like a natural progression to begin thinking about broader notions of the term.

The next thing you realise after reading all about the current attempts at context-awareness is that, well, they suck fail to be all that useful.

There are many very intelligent systems-based frameworks for building an architecture of sensors that can detect where and what you’re doing, and very detailed examples of software implementations that aim to interpret this sensor-based data to assist their users. It’s not that these frameworks and implementations are poor or under-thought, it’s simply that the technology isn’t there yet, and our expectations are too high.

Great Expectations

This isn’t our fault though – the term “aware” is loaded with expectation. It immediately conjures notions of Asimov-type robots that basically act and understand as we do – of computational uber-humans superior to us in every way – and ones that we will either grow to love or fear completely.

The problem is hinted at above – in the interpretation. Whilst we might have sensors that can pinpoint you on a map, know who you’re with, whether you’re talking or not, walking or not, whether you’re standing, sitting, or lying down, the problem lies in the translation of this sensorial information into meaningful, and accurate interpretations for software to use.

The optimist and sci-fi fan in me thinks that, one day, we will see a convergence of sensor technology and artificial intelligence that will provide useful scenarios to people. You might argue this happens already – a pilot’s cockpit springs to mind. But the fact remains that the detection of meaningful, dynamic and social context is a long way off.

Context is socially constructed

I’m working on a longer article on this at the moment, so I won’t go into too much detail. It is worth noting however, that whilst the cockpit of a plane is a highly controlled environment where all variables are know, much of what we would define as context is socially constructed. That is, its existence is fleeting, and only arises out of interaction between people, objects and the environment.

Whilst we may be able to detect your location fairly accurately, the context to your presence there is very difficult to detect. Test this next time you’re in a cafe – note all the different activities that are taking place there. The animated conversations, the quiet reading, the anxious waiting, the scurrying (or bored?) staff. For each of these actors, the place holds a completely different meaning for them – and hence, a different context.

Context Sensitivity

So if we can’t rely on technology to sense and interpret that kind of context, then what can we do? Well, I’m not sure I have any answers to this, but I would suggest that we first lower the expectations of and burden on our technology. When compared to “awareness”, a word like “sensitivity” seems much more realistic. We can’t do Bicentennial Man just yet, but what we can do is make intelligent assumptions about when, where and how our technology might be used, and we can selectively use sensed data to inform the design of our applications.

That is, I believe it is the role of design to augment the technology – instead of relying on technology to give us context awareness, we should rely on design to give us context sensitivity.

Thick Description

This week I finally received my ethics approval. For those who haven’t had to deal with an university ethics committee before, it’s a notoriously lengthy and tedious process. I managed to have my research methods approved within 3 months, which is about half the time it took my research partner – so understandably, I’m pretty happy!

As part of the ethics submission I essentially planned out every stage of the hands-on research I’ll be conducting with park rangers. I’m relying heavily on qualitative methods to uncover the behaviour, goals and habits of park rangers as they go about their jobs – focusing on who they communicate with, what information they impart and use, what decisions they make, and how all of this related to their notion of location. Essentially, I’m treating park rangers as a community with their own set of practices, and, through qualitative research, am hoping to uncover deeper links between themselves and the spaces they manage.

Thick description

A key aspect of almost all qualitative research is the notion of “thick description” – a term that appears in just about every text book on the subject. However despite it’s seeming importance, it’s a notoriously difficult concept to define. There have been numerous attempts, as documented in Joseph Ponterotto’s paper from 2006 (reference below).

In 1973, Geertz was the first to use the term in relation to qualitative research, and states the following:

From one point of view, that of the textbook, doing ethnography is establishing rapport, selecting informants, transcribing texts, taking genealogies, mapping fields, keeping a diary, and so on. But it is not these things, techniques and received procedures that define the enterprise. What defines it is the kind of intellectual effort it is: an elaborate venture in, to borrow a notion from Gilbert Ryle, “thick description”.

Denzin (1989) attempts to define thick description by comparing it to “thin description”. According to Denzin, thick description has the following features:

“(1) It gives the context of an act; (2) it states the intentions and meanings that organize the action; (3) it traces the evolution and development of the act; (4) it presents the action as a text that can then be interpreted. A thin description simply reports facts, independent of intentions or the circumstances that surround an action. (p. 33)”

Other definitions essentially equate it to doing ethnography – in that, the actual nature of ethnography is to gather thick descriptions. This is the most common link between the definitions – essentially, like ethnography as a practice, “thick description” can be said to provide context and meaning to observed actions, rather than simply recording the occurrence of an event in isolation. It’s more about recording the story of a fact, rather than the fact itself.

There are a number of ways to achieve the type of data that might be defined as “thick” – participant interviews, field observations, analysis of personal spaces and artifacts, and more. Diary studies are another well documented form, as part of a broader notion of a “cultural probe”. This is one which I intend to use with park rangers.

There’s an app for that

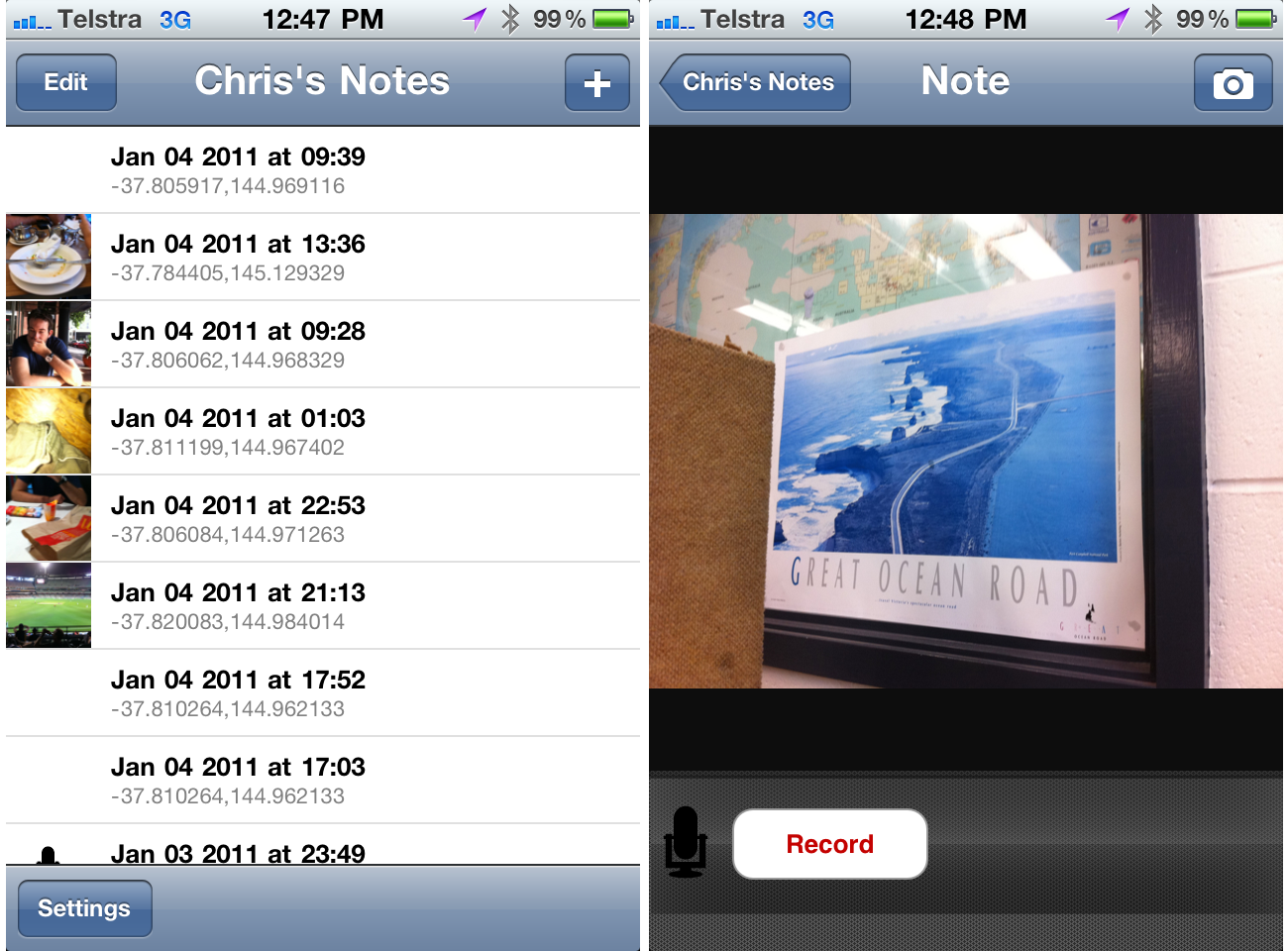

To this end, and given the extra-special role that location plays in my research, Reuben and I have built a custom application for park rangers, that asks them to provide thick descriptions of the locations they manage.

The application is mobile based (iOS specifically), and relies on a combination of GPS, photography and audio descriptions to gain a subjective sense of the spaces and places rangers make decisions about.

Each entry into this diary app is time-stamped and can be any combination of coordinate, photo and audio description. It’s this combination of audio and visual input that is the most powerful – given the nature of a park rangers job, audio descriptions are the most effective means of capturing the actions of rangers, and one that matches their current behaviour more closely than text based descriptions.

The goal is to create a low barrier to entry for rangers wanting to talk about their jobs as they’re doing them. Rangers will then be allowed to self-categorise/tag entries ex situ, before being visualised and used as discussion points in follow-up interviews.

The above screenshots are from the first functional version of the app, with many more improvements (particular design) to come.

Focusing the diary

To help guide the use of this application, we’re providing rangers with a set of guidelines on what types of information and input we’re interested in. Broadly, we’d like them to capture their interactions with other rangers, the decisions they make, the information they use in making these decisions. Given the role of location in all of these research questions, their entries will be analysed and visualised on maps to allow them to comment on the relationship between themselves and their environment.

We want to make this a fun activity for rangers, and we’ll be conducting kick-off sessions, and I will be following rangers into the field regularly to make my own observations and hopefully help overcome any confusion about the study before rangers are left alone with the application.

Wrap up

Thick description is a key part of the qualitative research I will be conducting with rangers at Wilson’s Promontory national park – I hope to uncover deep relationships between the rangers themselves and the locations they manage. As part of a much wider research program, we’ve designed and implemented a location-based diary study tool that will allow us to conduct remote research to be used as probes for further interviews.

Next for us is to build a visualisation interface for all this data – one that will allow us as researchers a way of making sense of qualitative data about locations, but one that will hopefully provide the basis of a knowledge management tool for Parks Victoria themselves.

References

Please note that the links below are to purchase the references I use in this post on Amazon. If you do find them interesting and decide to purchase them, I collect a small commission. Doing so will help support this blog (and my research!) in a small way, and I will be very grateful!

- Denzin, N. K. (1989). Interpretive interactionism.

- Geertz, C. (1973). Thick description. The interpretation of cultures.

- Ponterotto, J. (2006) Brief note on the origins, evolution, and meaning of the qualitative research concept “thick description.”. The Qualitative Report.

The missing network

One of the challenges of my project, from a technical perspective, is the non-urban environment it is situated in. Whilst it’s well and good to say that the solution will be context-aware and mobile, the reality is that the infrastructure that we take for granted in cities simply does not exist in a national park that is 3 hours from a major urban centre.

In one sense this is what (I hope) makes my research unique – we can’t gorge ourselves on infrastructure. 3G Networks are sparse, if not unrealiable, and WiFi is a pipe dream. GPS does exist and can be counted on, but when the core of the project is around the sharing and creation of knowledge, ideally in real-time, having an accurate reading of a ranger’s location is nice but not enough. There’s data involved, and quite possibly large quantities.

So – how do we facilitate this kind of knowledge ecosystem when the tubes are narrow, or don’t exist at all?

Well, the first thing a good researcher does is to peek over someone else’s shoulder. Although they may seem like polar opposites, the most similar environment I can think of that resembles a national park in terms of infrastructure is – wait for it – a plane.

This may change in the coming years (months?), but as it stands, planes have almost the same characteristics as a park. Sparse network access with absolutely no data connection, GPS works, but only if you’re even allowed to use your location-aware device at all.

Offline data storage is the obvious answer. WindowSeat App is an iOS application that stores offline data about points of interest you may be hurtling over at a given point in time. Its data set is fairly finite, so this model works well – however, in an app that is perceived as, and by necessity is, disconnected, how much of a barrier will there be to people wanting to contribute back to that data pool? Can we rely on people to sync, or should we be bold enough to make that decision for them?

The above picture is a phone tower disguised as a tree in Masai Mara National Park, Kenya

The End of Year Post

I’m technically a few days late for an end of year summary, so I’ll roll in a summary of the year-that-was with a preview of the year-to-come. Continue reading »

A synopsis

Inspired by a few different factors (Tricia Wang’s research overview, Patrick Dunleavy’s excellent “Authoring a PhD“, and this tweet – thanks Vicki!) I spent today going over my abstract and ended up writing a slightly more detailed synopsis of my thesis. Like everything on this site, the plan is to keep changing and updating this as thinking progresses.

In the meantime, I once again invite you to visit the abstract page – a brand new 600 words await.

Search

Geoplaced

This is a notebook exploring the gaps between geography, sociology, technology, science fiction and things between.

I used to write about my PhD here, which I finished in July 2013. You can download a PDF or order a print-on-demand copy of my PhD thesis.

Themes

- art (1)

- Augmented Reality (2)

- Brain Dump (17)

- Conducting a PhD (13)

- Context (6)

- essay-a-fortnight (2)

- fiction (1)

- Government (1)

- How to: Get a PhD (5)

- inspiration (4)

- Knowledge (15)

- Location (19)

- Methods (6)

- Mobile (2)

- Parks Vic (17)

- Place/Space (5)

- Research Questions (11)

- Technology (3)

- travel (1)

- ubicomp (7)

- Uncategorized (11)

- Visualisation (10)