Vault: Data Histories

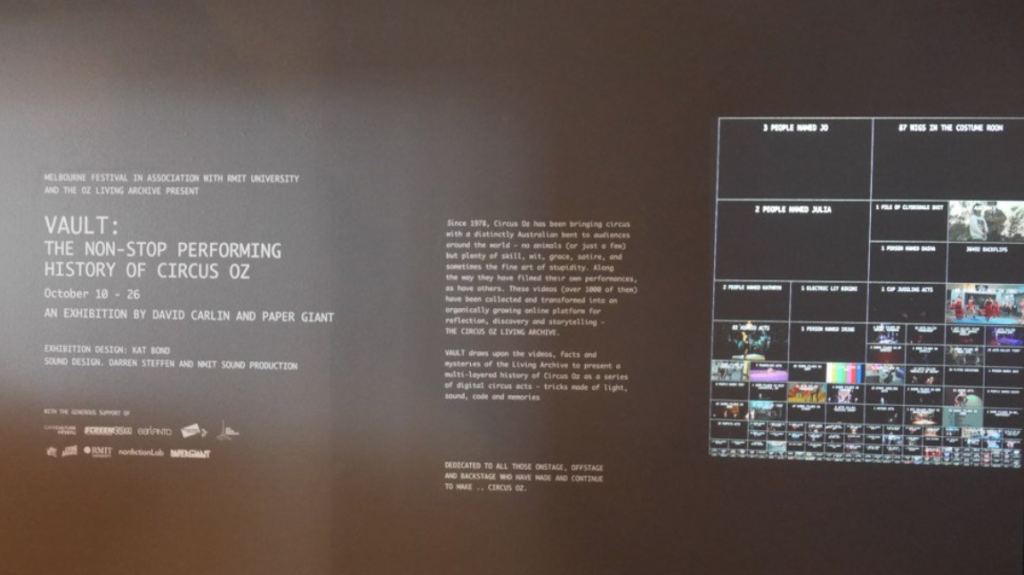

Last week we finished the install for an exhibition Reuben and I (and this other lovely team of people below) have been working on for the past four months. It’s a physical instatiation of a cultural archive for an Australia Circus company – a series of interactive and reflective pieces that use the material of the archive to dynamically perform a history of the circus company.

The exhibition is part of the Melbourne Festival, one of the largest art festivals in Australia. It runs from now until the 26th October at Melbourne’s Art Centre. That’s the one with the spire.

There’s almost too much to write about; the process of creating work for an exhibition, the stresses of installation week itself, the disappointment of some logistical challenges; but I just want to encourage people in and around Melbourne to go and check it out. I was involved in the creation of much of the interactive pieces, and it’s extremely pleasing to see months of work culminate into what seems to be a fun and engaging space.

It turns out that one of my favourite outputs from the exhibition is a catalogue Reuben made (downloadable on the exhibition website). The physical copy is available for free in the gallery, and is really nice to hold. It contains the history of the program, and most people involved wrote little essays. My one is called ‘Data Histories’, and I thought i’d post it here.

Data Histories

In March 2014, I visited Reuben at his home in the northern suburbs of Melbourne. We’d discussed our young collaboration, Paper Giant, for quite a while (we registered the company two years prior in a burst of enthusiasm) but our actual work together only really began at the start of 2014. We had our first project project – for a legal centre – and we were excited to finally do things our way. These trips out to the ‘rural studio’, as it came to be known, were always full of discussions around what exactly those ways might be, and we did as much design and prototyping on modes of working – on the ways we wanted to produce work – as on the work itself. We talked about how we wanted to do design and technology work that didn’t just serve a utilitarian purpose but would be both playful and challenging; work that posed questions, rather than assumed itself as an answer. Dunne and Raby’s book ‘Speculative Everything’ had been released in the months prior, and we watched from that ‘rural studio’ as a microcosm of interesting critical and speculative design studios across Europe and parts of the US began to pop up (or at least be amplified by Bruce Sterling’s twitter account). In this viscous mix; of conversations about modes of working, and amongst a growing set of politically-engaged and critical work, Paper Giant began.

On one of those visits, Reuben and I had talked about one day “doing an exhibition”. We spoke about it in the way you might speculate about a holiday – in vague terms, where dates and times are less important that defining the possibilities. Funnily, it was about a week later when Reuben mentioned the possibility of working on an exhibition for the Melbourne Festival with his academic colleague, David Carlin. The Festival this year is circus themed, and Circus Oz were going to be on tour. A circus-themed festival in Australia without Circus Oz is not a complete thing, and so the amazing Living Archive – the ghost in the machine that animates this exhibition – was to be put into action as the touring troupe’s proxy representative. Reuben and David had worked closely on the Living Archive project over the previous 3 years, and we recognised the Festival as an amazing opportunity to dive head-first into a form of technology and design experimentation that, as academic researchers, we had come to recognise as valuable, and that, as a company, we wanted to ingrain in ourselves. And so, together with David (and later Kat), we began to think about how the Living Archive could be put to use.

As a ‘thing’, the Archive is a complex assemblage of digitised VHS, a video encoding system, and database tables, columns and rows. This material infrastructure finds itself stored in hard-drives on servers that physically sit in an air-conditioned room half way around the world. On top of this infrastructure, the archive is also a set of representations of this material – the public site for the archive (archive.circusoz.com) is an representation presented as a user interface; a number of screens that allow its users to assemble, interrogate and view the ‘stuff’ of the archive in different ways. The piece between the ‘infrastructure’ and the ‘interface’ is another important part of the archive – an application programming interface (API). The API is a software layer that allows the material infrastructure of the archive to be put to use – to generate interfaces and representations of the ‘stuff.’ It is this piece of the archive that allows the public website to be made and it would also allow us to get at the videos, data, and data-about-data in new ways. The API was what we wanted to play with.

Early conversations about this exhibition revolved around the use of the API to create absurd gadgets and software representations that avoided traditional representations of ‘data’. Why not have a slot machine that pulled random keywords from the database, and showed you a video that “matched” those keywords? Pull the arm, and it gives you a video. We replaced the arm with a button, and turned down the video a bit (there’s a lot of that already), and voila! The Poetic Randomiser. This is an Act that highlights the poetry of imperfect datasets, and the messiness of words that are stored and processed algorithmically, extracted from their context.

We also started to think about the time and scale of the exhibition, and what that would allow. We took this to two extremes: the frantic, spectacular looping of animated gifs and videos you see throughout the exhibition, where scales of time are best counted in seconds; where we’ve attempted to highlight the relationship between time, repetition and spectacle. At the other end of the scale, the Marathon of Marvels is an Act that plays the whole archive, unfiltered and in real-time, over 110 hours.

Not all of our hair-brained schemes made it into the exhibition. What is now known as the Magic Curtains started off life as a series of videos that would either fast forward or rewind based on your direction through the room, against a wall that would have movement sensors attached. We thought it’d be a clever way of “playing with notions of progression in historical interpretations”, and of making the works interactive in some way. We tried to do this, but gave up after 2 frustrating weeks. You’ll notice we’ve listed “compromise” as a key ingredient in this Act.

Other ideas that didn’t make it, for some reason or another:

- A button that would make the whole exhibition stop.

- A sensor that noticed when you walked into the room, and logged you to the database.

- A sculpture of springs with screens that jiggled as you walked past, like a robotic busker.

- A screen on a rope that swung around, like a trapeze artist.

- A ticket machine that would print out the words of the poetic randomiser, with a URL where you could view the associated gif.

- A roomba vacuuming robot that followed you around, yelling “Roll up! Roll up!”

You can see how some of these may have been a bit scary for children. But you can also see that, between the absurdity and playfulness of these ideas, a certain theme emerges. What we hope to have achieved is a blurring of the lines between the physical and the digital, the circus and the database, “fun” and “data”. More prosaically, behind the playful facade, we wanted to show that digital traces created by people – actions stored in databases – can be mobilised for purposes other than surveillance, reduction, or analysis. Delight, parody and play are important tools in a contemporary political and social context where the digital traces we produce are being contested, regulated and mobilised by increasingly paranoid surveillance states. We have tried to surprise and delight, but we haven’t shied away from the politics of data. The History Teller shows an example of what can be known (and more important, what is missing), from the counting of databases. Whilst there is a form of knowledge embodied in this act, the numbers and short clips spat out by the code and projected onto the wall are an obviously limited perspective of the Circus. The projection could, at any one time, show performers from over four decades, but each number it calculates are those same decades, boiled down. And the Data Logger, at the back of the room, reminds people that the actions that occur in the exhibition itself – including actions triggered by you – can and are being recorded. When ‘history’ is positioned as something deterministically and passively written by technology – as it often is in an era of ‘Big Data’; of ubiquitous sensors and cheap data storage – it pays to be aware that the ways that ‘history’ is recorded and later told are not something you have control over. In this way, we have designed the exhibition to play off between expected and unexpected ways of telling a data-history. We’ve also designed the exhibition as a continuation of the database itself. You are quite literally walking the archive, and your actions here influence and shape it.

Vault – this exhibition – is a playful instantiation of a code-space: a physical environment that is so enmeshed with its constitutive software that it fails to be the same space without it. We want you to have fun here, to be mesmerised by the feats of performance captured on video from times past; to be hypnotised by the spectacles of repetition and colour that have been assembled by code we’ve written. But we also want you to think about what digital traces mean in the context of remembering and forgetting. Think about what is being told, and what is missing; what lives between the gaps of the videos, text and screens you see, just off the corner of the screen, or in the frame after the last in a loop. It is in those gaps that another history of Circus Oz is being performed, non-stop. There’s no mistaking that there is something remembered here, though. By walking through the exhibition, you are both witness to and participant in a certain form of data-history. The database is being assembled into representations, and those representations perform around you. But recognise, too, that it’s your interpretation of it that makes this a history of any meaning.

The Vault Exhibition is part of the Melbourne Festival, and is showing at the Melbourne Arts Centre until the 26th October, 2014.

Search

Geoplaced

This is a notebook exploring the gaps between geography, sociology, technology, science fiction and things between.

I used to write about my PhD here, which I finished in July 2013. You can download a PDF or order a print-on-demand copy of my PhD thesis.

Themes

- art (1)

- Augmented Reality (2)

- Brain Dump (17)

- Conducting a PhD (13)

- Context (6)

- essay-a-fortnight (2)

- fiction (1)

- Government (1)

- How to: Get a PhD (5)

- inspiration (4)

- Knowledge (15)

- Location (19)

- Methods (6)

- Mobile (2)

- Parks Vic (17)

- Place/Space (5)

- Research Questions (11)

- Technology (3)

- travel (1)

- ubicomp (7)

- Uncategorized (11)

- Visualisation (10)