Emerging outlines

As an activity today I went through this blog and conducted a card sort on the posts. What emerged from it was a rough outline of my overall thesis (and the realisation that I’ve written many more words than I had originally thought). There is a lot of manipulation to get these words into a submittable form, but this quick glance through has netted me close to 15,000 of them. This is minus any of the notebook content and thinking I’ve done, my notational velocity library, formal papers (6+), and various documents written around my case study and methods.

I’m feeling better about finishing by September now. More importantly, this exercise has given me the start of a document that has an concrete outline, and will slowly evolve into a finished thesis.

Notes

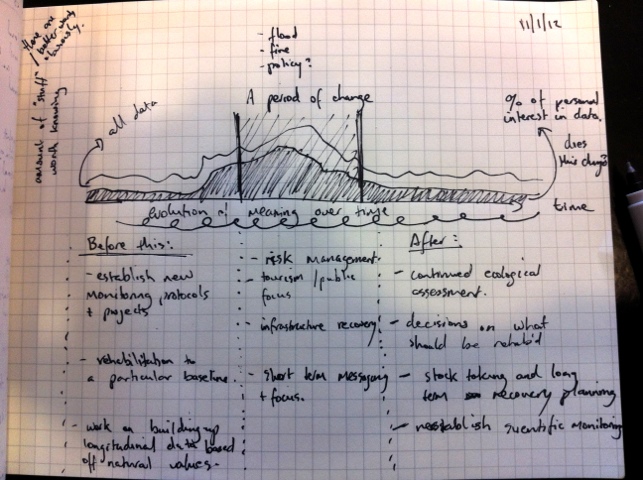

I’m increasingly relying on my notebook to test out ideas and document progress. In the last 3 months, there’s been about 100 pages of content similar to this: trying different ways of analyzing data, and prototyping chapters. It feels much less formal than this blog, but today I was suddenly struck with the realization that if this notebook was lost, so would the majority of the most recent thoughts on my phd.

So I’ll include a picture of important ones here, every so often. Beyond that, I’ll let the note speak for itself.

Landscapes

2011

To curb off a bit of the ol’ thesis anxiety, I thought I’d make a list of things-I-did this year. In no particular order, here are the things I liked (and possibly didn’t) this year.

Writing/Talking

My university (and supervisor) are great at encouraging and pushing their graduate students to write and publish their work. This year was no different, with a couple more publications to add to the list:

- A paper for The International Cartographic Consortium conference around context-awareness in visualising geographical information. Presented in Paris, in July.

- Doctoral Consortium paper for Mobile HCI. Presented in Stockholm, in September.

- A book chapter in an upcoming RMIT publication around future social contexts of Geovisualisation.

- Full paper for the LBS 2011 conference. Presented in Vienna, in November.

- A visit to ARSyd to talk about how we make sense of location based data.

Apple’s WWDC

In June I attended Apple’s developer conference in San Francisco. I learnt quite a bit, but the most inspiring thing was seeing so many independent designers and developers working on things they love, and not starving during the process. I traveled with Reuben, who I highly recommend to anyone needing to share a hotel room. He doesn’t snore.

Paris

I had the opportunity to stay in Paris for the entire month of July – a week for the ICA conference, with three weeks tacked on to the end. Again, I met some great people and has some very interesting discussions about my work. I also rented a small apartment in Belleville, and worked on my french accent a little more. Weh.

Misc (or: stuff that doesn’t sound as cool).

After another year of “being a PhD student”, I feel like I’ve learnt some valuable lessons about how to be one of these wretched creatures. Particularly, I’d like to point out a few things about having a research question and involving others in your work:

- Let the data speak for itself. Do not try to shoe-horn your research into your own pre-designed agenda. When you first start something like a PhD, you can often get excited (and overwhelmed) by the number of possible directions you might take. Of course, you then choose one of them – generally something you really like, or care about. In a beautiful twist of fate, you eventually learn that you can’t choose what you observe. Research is cyclical, and you need to pay attention to what your data is telling you at all times. Your research won’t always be what you thought it would be.

- You need time. About half way through the year I stopped working completely, and became an actual full-time student. Granted, it was the “working” part that eventually allowed me the freedom to do this, but clearing my plate of all other commitments was one of the best decisions of the year. You need to be fully immersed in a research thesis, and even small, one day a week commitments can be distracting. You might lose a little bit of industry experience, but you’ve got the rest of your life to get that.

- Talk to people. Some of the best ideas and advice I’ve received have been in casual conversations with people in similar situations to me. At a pub. In a cafe. In a national park. Having a whinge every now and again is very important, but you should always take up any opportunity to speak about what you’re doing. Even if it leaves people utterly confused, hearing yourself explain something in a slightly different way will often spark new and exciting leads to follow up on. It also gets you out of your stuffy office, and highlights the value and importance of communicating your work effectively.

2012

Next year is my final year (hopefully), but I’m excited to see where it takes me. There probably will be a few less international sojourns, but I’m looking forward to producing a semi-decent thesis and beginning to explore where that might take me.

Woven Stories, Layered Landscapes

Parks Victoria have produced a video on Aboriginal Cultural knowledge, a great introduction to the notion that people, practices and a landscape are tightly related.

People say that after they have been in an area for a while, they start to become a reflection of that environment. Sometimes, the environment starts to reflect the people. This connection between people and country is what powers the life essence and intrinsic memory imprinted in that place. It is this absorbed energy that continues to draw people there, for the same reasons, for countless generations.

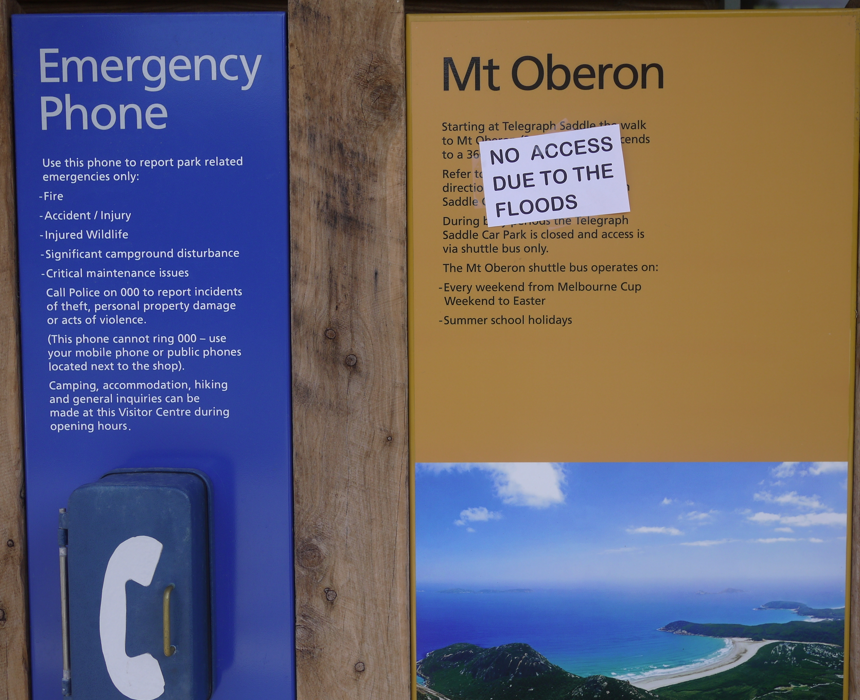

Flood Recovery as a Space

Whilst the park is open to visitors, issues of access and accessibility are still persistent. These images above are taken mainly in “tourist” areas, with the signage communicating to the public. However, the issues are present for everyone: people can’t get to where they were able to previously.

How is this effecting the information being collected in the park? Monitoring equipment has been disrupted, and simply can’t be gotten to. At the same time, the focus of work has shifted from ecological management to getting visitor infrastructure back up to scratch. The flood has been a hugely disruptive event that has changed how people (both public + rangers) interact with the park – and therefore, their understanding of it.

The space of a flood recovery is very different to that of normal park management. The rangers are still in that space.

Follow the thing

Eight months after the flood at Wilson’s Promontory, Tidal River has been (kind of) re-opened to the public. People are able to stay in the park itself (fortunately, this includes researchers), but many of the surrounding trails are still in need of repair.

Status update aside: I spent two days in the park this week conducting interviews with staff. The interviews consisted of two parts: using the diary entries from a previous study as probes in interviews, to dig in to what the life of these media objects might be within the organisation; and an examination of the “personal geography” of the park, for each interviewee. This was elicited through drawings of the park – more about these in another post.

Entries as probes

I just want to give a brief summary and background on one of the methods I used in the interviews. The entry-as-probe section is a basic attempt at “following-the-thing” (Marcus, 1995) – an ethnographic method for tracking digital and media based objects across multiple sites, in order to discover their role in social processes and contexts. The key phrase here is multiple sites; despite my study area being a geographical location, its focus is on the social and organisational contexts around this location. It is not investigating what happens in the cartesian representation of the park (i.e. what you see on a traditional map), but what happens in a broader social context in order to manage that area. Without getting too sidetracked on writing about my actual thesis: it’s important to investigate the flow of information and people that make park management possible. Marcus’s method boosts the status of an “object” (in this case, a dairy entry) to an equal actor in the construction of meaning, rather than a tool to be used by people as they themselves do the construction. As such I want to investigate the potential role of these created “media” objects in the ability to trigger different interpretations for people in varying roles across the organisation.

The next step in following-the-thing is the city office. Taking entries from the park and putting them in front of people unfamiliar with it will hopefully provide some interesting insights into the different understandings they have about Wilson’s Prom.

This is all in attempt to examine the different geographies that exists within Parks Victoria. The differences between the park and the city will be a key one, I’m predicting.

Reference:

Marcus, G. (1995). JSTOR: Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 24 (1995), pp. 95-117. Annual review of anthropology.

The park as a design space

My case study site is Wilson’s Promontory, a national park situated in the rural south east of Victoria, Australia. Whilst my thesis will broadly discuss the roll of environmental understanding (from a cultural geography perspective) in the design of technology for use in these types of settings, the “practical problem” I’m faced with is to make something for the park and it’s rangers. As an exercise it’s worth thinking about the space of the park as a context for design, exploring the implications this may have and distilling what aspects of this environment might be meaningful for design.

The park is a (semi) natural place

Most technology is designed for urban contexts, by designers with urban perspectives. As Bidwell & Browning (2010) explain, this monocultural approach to technology can lead to significant amounts of dissonance when it comes to use in rural settings. Screen glare is a common example of technology going fundamentally wrong in a natural setting – but other examples, such as the unsuitability of social networks for rural lifestyles, have also been explored. It’s important to challenge assumptions about traditional (i.e. urban) design approaches when moving away from cities and into natural and rural settings.

So, as a starting point it’s important to define what a “natural place” is. Bidwell & Browning give an definition based on two criteria: population density, and access to infrastructure. A natural environment, according to them, is sparse in human population and has limited built infrastructure. The park is an interesting landscape in this regard, because it has a combination of “urban” settings along with completely unpopulated, infrastructure sparse locations.

Population

- The park has a small set of staff who live on-site in Tidal River (described as a “small town”).

- Most staff commute to the park from surrounding rural centres, and a significant portion of the park management and planning happens in administration hubs in nearby Foster, and further away in the CBD of Melbourne.

- Tourist populations fluctuate wildly, depending on the season, and (primarily) school holiday schedules.

- The flow of people to the park is therefore predictable, but consists of extremes that make it difficult to categorise the park as a “natural place”, consisting of sparse populations.

Infrastructure

- The camping grounds of Tidal River have been referred to as a “small town”, with all the comforts and amenities expected of a highly frequented tourist site. It even has an outdoor cinema to cater for large, restless school groups.

- Highway quality roads provide easy access to Tidal River. Most of the frequented tourist destinations in the park are easily accessible by walking trails off the main road. Similarly, ecological research areas, and other general “areas of interest” for rangers are close to the main road between Yanakie (at the park’s entrance) and Tidal River.

- Walking trails provide access to a large portion of the park not accessible by vehicle.

- Mobile phone reception is generally mapped to the tourist population hubs, but it’s possible to get a signal is most areas of the park that are human accessible.

So, on the one hand we have a tightly “cultivated” area of the park – those most frequented by tourists, and heavy on built infrastructure. On the other, we have a largely preserved or “uncultivated” areas – where built infrastructure is extremely limited. It is at once a “natural place” – as defined by Bidwell & Browning – but also a tourist space, where populations fluctuate and infrastructure is at least as developed as in surrounding town centres. All the while, the digital infrastructure is not discriminating – cellular towers provide adequate coverage to most human-accessible areas.

Given this dichotomy of populations and infrastructure, it’s difficult to classify the park as either a “natural place” or an “urban environment”. It has elements of both, but it is truly neither. Is it right to call somewhere a “natural place” if you’ve got full reception on your iPhone? If it’s a particularly busy day, with many thousands of people in the park, do we suddenly call it “urban”, despite being surrounded by native flora and fauna?

Emerging geographies as a design space

Given the difficulty in classifying the park as either “natural” or “urban”, it’s worth examining the park as a set of different geographies that are not in competition with one another, but are complimentary perspectives that emerge through interactions between and by people (particularly, rangers) in the park. The previous two posts have begun to address varieties of these perspectives – how the movement and flows of rangers construct a particular perspective of the park space, and how the geography of infrastructure might act as an index to the knowable areas of the park.

Some further “geographies” that seem to be coming out of interviews and diary entries speak to the follow categories:

- A geography of emotions – How emotive connections are formed to the landscape, and the particular form of knowing this invokes. This is salient in the time surrounding natural disasters (such as fires and floods).

- A geography of administration – This was hinted at above, with mention of the differing geographical locations of the management of the park. There are those situated in the park itself, but also those in nearby rural centres, and the metropolitan central office. The flow of information, decisions, and people from and to these locations is worth exploring.

- A geography of indigenous knowledge – Parks Victoria is working on co-management strategies that incorporate the traditional land-owners in the management of the park, and are working towards ways of including the knowledge of the landscape with current practice.

References

- Bidwell, J. & Browning, D. (2010). Pursuing genius loci. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing.

Geographies of access

Following on from the last post on an analysis of the movement of rangers, I’d like to discuss another interesting (if not obvious) finding from the diary study. That is: that accessibility dictates what is possible to know.

Access and infrastructure are common topics in ubiquitous computing literature – access to “digital space” is dependant on infrastructure that supports it: a wifi signal, 3G telecommunications towers, an internet cafe. Similarly, infrastructure can dictate the ways we navigate a space – we might choose a cafe to eat at depending on the likelihood of an internet connection; less “digitally” focused, the car route we choose to one destination depends on the roads that exist, but then also our knowledge of the likely traffic conditions of those roads. In each case: access to infrastructure (and the quality of that access) influences our behaviour.

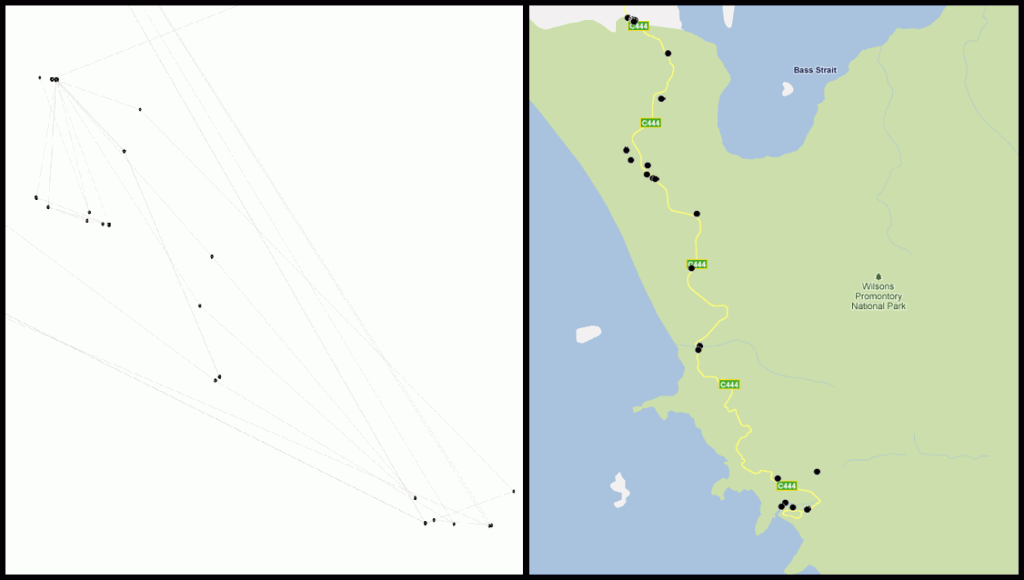

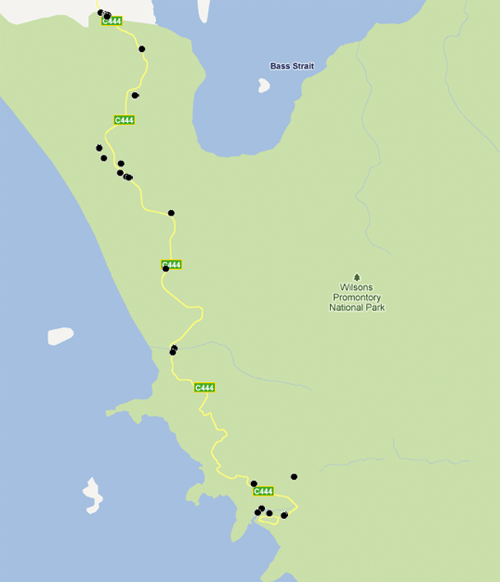

This isn’t as obvious in the image I generated for the previous post, but after doing a lazy google map of the data the trend is clear: almost all entries were made on or near a road. Even those taken “off road” were generally not far from it – judging from conversations with rangers, these places are generally within walking (or equipment-carrying) distance of their vehicles. Also, the few outliers visible on the map are taken along walking tracks, rather than roads. The volume of recordings on a place depends on the bandwidth of the access. Roads are high bandwidth, walking tracks less so – dense scrub: very low.

Some questions that this raises:

- How can you design for discovery of “new” knowledge when data-rich areas are also, by necessity, the most familiar?

- What opportunities will there be for technology to encourage exploration of new areas?

- How will existing infrastructure and accessibility to the park limit the potential for exploration?

Geographies of Movement

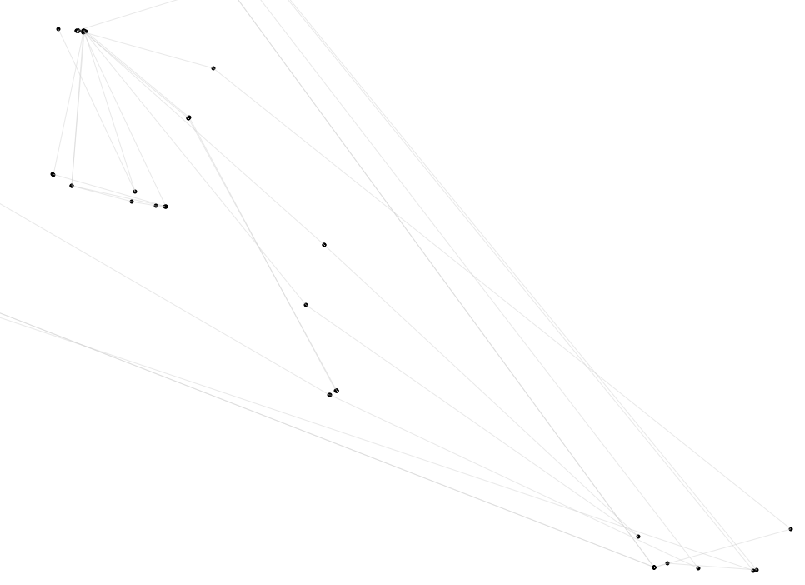

Over the last few months I’ve conducted a mobile diary study with rangers at the study site, Wilson’s Promontory National Park. Six participants were asked to record a number of entries as they went about their daily activities: a) Things they wanted to show other people, b) interesting observations for themselves, and c) recollections of a past experience, amongst others. Analysing the qualitative contents of these entries has revealed much about the connections between Parks Victoria staff, the park itself, and their tools and technology. At the same time, I’ve been doing some programmatic/quantitative analysis of the entries – mainly, the combination of timestamps and the attached location data.

I’d like to give a quick overview of some of the early findings of the study. Before that though, it’s worth talking a little about movement, and how this has come to be understood as a key source of environmental understanding.

Movement is knowing

Movement and mobility are becoming key concerns in the areas of sociology, human geography and ubiquitous computing. The sociologist John Urry (2006) suggests that mobility – the flow of information, people, and goods – rather than fixed societies will be a key concern for sociologists this century. Similarly, in human geography the notion of unblocked space (Thrift, 2003) is one concerned not with fixed points, but with movement and flows through these spaces. Thrift argues that space should be viewed not as a boundary around these flows, but as the flows themselves. In this sense, movement through a space is the definition of it.

The synthesis of these and other theories are starting to inform elements of ubiquitous computing research. Distinctions between “space” and “place” have been used by CSCW researchers as a means of separating a “socially constructed” place, and the objective space for some time. By focusing on flow and mobility, researchers now to also view space as a social construct. As such, it’s possible to argue that our environmental understanding is tied up in our constructed notions of space. Bidwell et al. (2011) demonstrate this by looking at rural knowledge traditions in Africa which are often explained as spatial relationships. Brewer & Dourish (2008) similarly present cultural accounts of space, and highlight that much of our technology relies on assumptions about how we interact with our environment.

Both of these papers discuss spatial relationships in the context of knowledge, and highlight ways in which technology may be better designed to more closely match different conceptions of space.

The acts of Rangers

Ranger’s work is to manage the park; they do this through interacting with it, and it is through these interactions that they produce knowledge. The diagram above shows where diary entries were made (with a dot), but also the path they took between entries. Most entries were reports of things that happened between the last entry and the current one. This means that much of what rangers thought to be important happened on the lines – that is, in their movement between places. Keeping with the notions of flow and mobility mentioned above, the lines can be viewed as the space of the park, as enacted by the rangers. These abstract dots and lines, for them, are one way of representing the park as they act in it.

This picture also obviously emerges a sense of “hubs” – areas where rangers go back to, and move between commonly. I’m guessing most people familiar with the park will be able to pick out where these areas actually are based on this diagram. It’s these places where knowledge “from the field” is primarily shared, interpreted and enacted upon.

The lines going off the screen also indicate that the management of the park occurs not just in the park – the “geography of management” includes administration hubs in the city and surround areas of Gippsland. Whilst this image is centred on the (invisible) geographic area of the actual park, a significant portion of entries occur “off site”. The park is just one place in the network of movements and actions carried out by rangers.

There’s a lot more to say around this study. As I start writing the thesis chapter I have planned, I’ll keep posting refinements. In the meantime, enjoy the reading below!

References

Bidwell, N. J., Winschiers-Theophilus, H., Koch Kapuire, G., & Rehm, M. (2011). Pushing personhood into place: Situating media in rural knowledge in Africa. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 69(10), 618–631.

BREWER, J., & Dourish, P. (2008). Storied spaces: Cultural accounts of mobility, technology, and environmental knowing. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 66(12).

Thrift, N. (2003). Key concepts in geography.

Urry, J. (2006). The new mobilities paradigm. Environment and Planning A.

Search

Geoplaced

This is a notebook exploring the gaps between geography, sociology, technology, science fiction and things between.

I used to write about my PhD here, which I finished in July 2013. You can download a PDF or order a print-on-demand copy of my PhD thesis.

Themes

- art (1)

- Augmented Reality (2)

- Brain Dump (17)

- Conducting a PhD (13)

- Context (6)

- essay-a-fortnight (2)

- fiction (1)

- Government (1)

- How to: Get a PhD (5)

- inspiration (4)

- Knowledge (15)

- Location (19)

- Methods (6)

- Mobile (2)

- Parks Vic (17)

- Place/Space (5)

- Research Questions (11)

- Technology (3)

- travel (1)

- ubicomp (7)

- Uncategorized (11)

- Visualisation (10)